JERRY BLEEM: STILL

Essay by Anne Harris

Riverside Arts Center

September 6 – October 17, 2020

It is only through examining history that you become aware of where you stand within the continuum of change.

–John Lewis, from Across That Bridge: Life Lessons and a Vision for Change (2016)

Detail: Jerry Bleem, Collateral Damage [Uncorrected], 2009, correction fluid, lint from U.S.A. flags on lint roller sheets, book form, 7.125” x 16.75” (closed); 7.125” x 33.5” (open)

Pittsboro, N.C., July 16 (AP Photo/Gerry Broome)

In this moment of political polarity and pandemic, of Black Lives Matter, of mass international protest, lowered flags, toppled statues, defaced monuments, of interconnected crises and unchecked, irresponsible, unconscionable government, Jerry Bleem has decided to reopen his Nationalism series.

This body of work began in 2003, as a response to our invasion of Iraq. Its intention: to invite slow contemplation of the complexities, nuances and contradictions that surround American patriotism.

In response to this invitation, the thoughts and opinions that follow are mine.

—Anne Harris

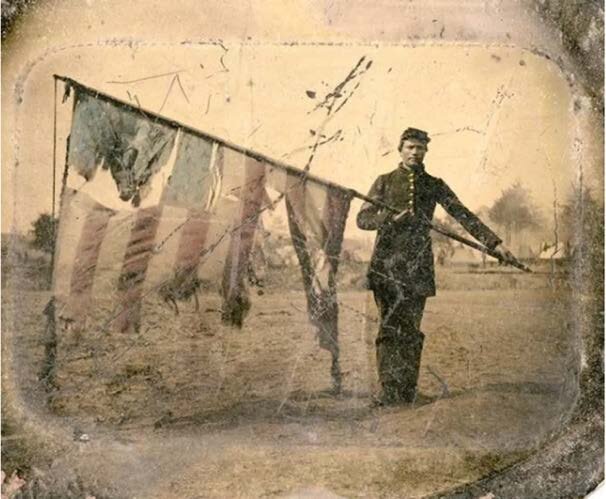

Portrait of Soldier with American Battle Flag, photographer unknown, 1863, tintype, 4” x 3.15”, John M. Sell Civil War Collection, California State University Northridge, Library Special Collections

The Other Flag

On the final day of the Battle of Gettysburg, Corporal Joseph H. De Castro, as always, ran into battle armed only with the Massachusetts flag. His job was perilous; he was both rallying point and artillery target. That day he used his flag’s staff as a weapon, to overpower the Confederate flag-bearer and seize the Confederate Army's 19th Virginia Regiment flag. For his valor, Corporal De Castro became the first Hispanic-American to receive the Congressional Medal of Honor.

The Virginia banner De Castro retrieved, called the rebel flag or Southern Cross, is the ubiquitous symbol of Southern heritage, individualist rebellion, and racism. Today, we find it in the meeting halls of the Daughters of the Confederacy and at the annual KKK “kookout” in Madison, Indiana. It’s carried by anti-mask protestors in Lansing, Michigan, Trump supporters in Odessa, Texas, and (oddly) soccer fans in southern Italy. Only last month did it cease, finally, to wave above Southern state-houses.

19th Virginia Regiment flag, American Civil War Museum, photograph by Katherine Wetzel

Also last month, here in Chicagoland, LaShandra Smith-Rayfield drove to her local beach in Evanston to confront a family of beach-goers who’d hung their Confederate flag beach towel across the fence behind them. Most startling about this encounter was not that a white family would display this controversial symbol, but that immediately, rushing to their defense, was a veteran (apparently Hispanic) who declared, “I fought for that flag!”

How would De Castro react to this? Smith-Rayfield’s response, “My flag has fifty stars. That flag right there is my swastika.”

Screenshot, cell phone video by Lashandra Smith-Rayfield, Lighthouse Beach, Evanston, IL, July, 2020 (individuals depicted here remain anonymous)

History is written by those who fund it. That a veteran in 2020 would conflate the Southern cross with the stars and stripes is a product of 140+ years of historical white-washing. Funded by the Daughters of the Confederacy and their ilk, Southern secession has been sentimentally redefined as the noble-in-defeat Lost Cause pined for in Birth of a Nation and Gone with the Wind. In this spirit, the rebel flag was hoisted from Rome to Tokyo by white Southern servicemen during WWII (“This is one war we’re gonna win,” said a major from Atlanta). By 1948 it was officially displayed on U.S. bases; ironically, the same year Truman mandated U.S. military integration. We see the results today in the defender-of-the-beach-towel, who spoke up to support freedom of expression for those wielding what Smith-Rayfield called “a racist symbol of hate,” but did not support the free-speech of Smith-Rayfield, the black woman who challenged them.

Union flag with thirty-three stars, flown over fort Sumpter

This Flag

American political conflict, like our two-party system, is often described as a clash of opposites: conservative vs. progressive, left vs. right, rich vs. not rich, white vs. not white, even capitalist vs. socialist. These binary break-downs push us toward polar estrangement. Let’s consider a different pairing—the relationship between nationalism and pluralism.

“America First” is nationalism—the exaltation of one nation above others. “Make America Great Again” is also nationalism, as is “build a wall,” and “go back to where you came from.” Nationalism is us-against-them, an insular mandate to stay as we were. This thinking underlies xenophobia, racism, and other bigotries. It’s fueled by competition and fear. The American flag is most wedded to the Confederate flag when it’s viewed as nationalist—a symbol of superiority and exclusion.

Matt, Herron, “Alabama, the march to Selma,” 1964, from Matt Herron, Mississippi Eyes: The Story and Photography of the Southern Documentary Project, University Press of Mississippi, 2014

In contrast, pluralism is inclusion. It’s a belief that diversity (of people and opinion) leads to prosperity. It calls for coexistence, shared power, tolerance and equality. The pluralistic tent covers all of America and its varied ideologies and principles. However, this includes nationalism, which leads to moral contortion.

How do we prioritize tolerance while tolerating intolerance? The answer—badly. The unequal application of human rights makes us a sloppy mish-mash of inspiration and hypocrisy. We end our flag’s salute, “with liberty and justice for all,” yet who picked the cotton that formed the thread that became our first flag? Who, under the hand (or knee) of the law, sanctioned by our Constitution, is most likely jailed? Most likely killed?

On May 25, George Floyd was murdered. A Minneapolis police officer, one knee on Floyd’s neck, his hands in his pockets, looked into phone cameras with indifference as Floyd begged for his breath and his mother and finally died. We all saw it.

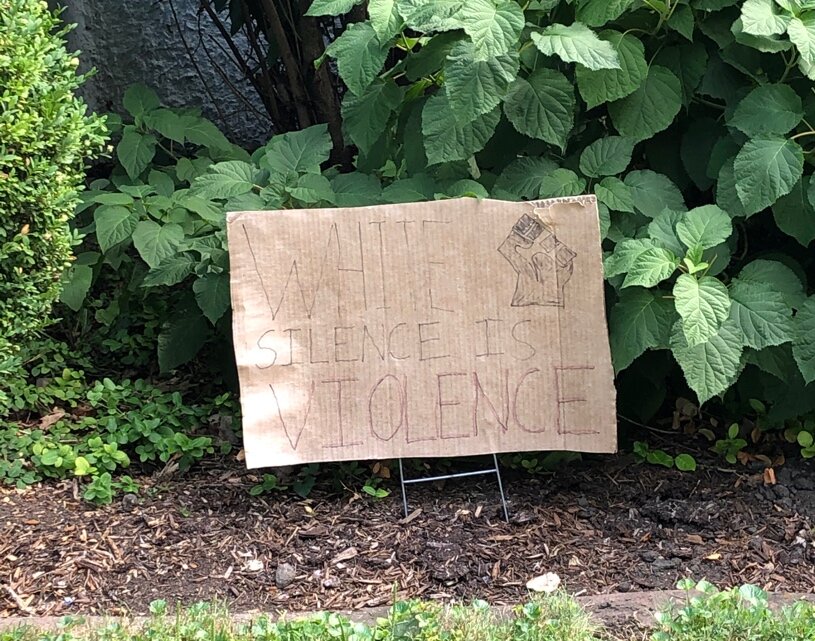

There followed (and it’s happening still) a massive wave of Black Lives Matter protests and an ongoing purge of monuments, symbols, names and flags. Even Mississippi banished its Southern cross, as did the Pentagon; the rebel flag can no longer be displayed on U.S. bases. These last two months BLM has grown historic in size, breadth, and plurality of support. They are now tackling Martin Luther King’s unfinished battle for Economic Justice. This struggle—between what we were, what we are and what we should be—is an American reckoning. Can we remake ourselves?

Riverside, IL, Lawton Road, August 17, 2020 (photo by Anne Harris)

Who made America,

Whose sweat and blood, whose faith and pain,

Whose hand at the foundry, whose plow in the rain, Must bring back our mighty dream again…

O, yes,

I say it plain,

America never was America to me,

And yet I swear this oath—

America will be!

- Langston Hughes, from Let America be America Again (1936)

Nationalism Still

Jerry Bleem is a collector. He’s collected Sacred Hearts, and also Crucifixes from around the world. These are hand-made, unique and sometimes awkward. They reflect their varied makers and diverse cultures. Their range also reflects Jerry, who is a Franciscan friar, Catholic priest, teacher, writer and artist. In the time I’ve known him (twenty-two years) he has also systematically collected things we throw away: termite wings, cancelled stamps, the plastic tabs that close the ends of bread bags, and in a large jug, decades-worth of fingernail and toenail clippings—often donated to him. He is “drawn to materials that have had a life” before him. Jerry has yet to use the clippings, but the rest of this saved detritus has become art—each “collection” a body of work. He joins these small units together using some kind of stitching. The stitches too are made of unexpectedly ordinary material. For instance, he makes wondrous things with desk-top staples.

In his series, Nationalism, Jerry begins with well-used American flags. These come from places we’ve all seen such as the porches of homes or the roofs of gas stations. Their fabric holds their age and purpose— a daily testament to the loyalty of a homeowner or the commercial branding of “all-American” products. They are weathered, frayed, bleached and stained. Jerry transforms them into contemplative objects. He does this by cutting each flag into a single, narrow, continuous strip which he then crochets into artwork ranging from wall-sized tapestries to palm-sized soft sculptures.

The crochet stitch—a loop—slows him and us down. Each stitch measures time. In the making, crochet invites an interior methodical focus. In the seeing, we are drawn to the hand-done-ness, the tactile irregularity, and to the rhythms, patterns, unexpected shifts and flaws that attract us generally to hand made well-crafted things. We feel the maker’s fingers working. We are tangibly attracted.

This intimate by-hand process negates the mass-production of the repurposed flags, as well as their generic public function. Instead, crochet evokes earlier hand-stitched banners, ritualistic repetition, as well as ceremonial hand-carrying and hand-folding. The pieces themselves are organically patterned, with weathered color and seductive surfaces. They invite aesthetic pondering and art history connections, from Jasper Johns to David Hammons, Faith Ringgold and Barbara Kruger—artists who have likewise depicted, distorted and physically or symbolically dismembered the flag. Their challenge, like Bleem’s, lies in their relationship to politics and culture. They all build on our history of displaying, manipulating and dissembling the flag in celebration, ceremony, fashion, decoration, propaganda and protest.

Faith Ringgold, Flag Story Quilt, 1985

David Hammons, African-American Flag, 1990, dyed cotton, 59” x 92 ¼”

In the end, Bleem’s work is distinct. Each piece is a meditative muse. We ponder it objectively as a physical sensory object, and subjectively as a prompt for interpretation, imagination, debate, and (in my case) historical excursion. By using our flag as both material and subject, Bleem transforms it from the symbol of American patriotism into a metaphor for our complicated, contradictory history.

Jerry Bleem, Remnants of My Considerations, 2009, unraveled U.S.A. flags in flag display case, 12.875” x 25.625” x 3”

I want to explore the link between the U.S.A.’s course of action and the lives of its citizens, between group consciousness and the dissension that exists within any assembly, between the public and private.

By rearranging the surface of the flag, I hope to turn it from something familiar into something that must be deciphered. In the process, I hope a viewer might wonder how the flag (to which we ‘pledge our allegiance’) also measures our failure to extend ‘liberty and justice for all.

--Jerry Bleem

Jerry Bleem, Camouflaged Nationalism [Select Your Allegiance Carefully], 2009, U.S.A. flag, Thai flag, patriotic bunting, nylon cord, dimensions variable (6’ x 9’ as photographed)

Jerry Bleem, The Flag of the Un-United States of America, 2006, U.S.A. and Texas flags, 54” x 90”

No, I’m not an American. I’m one of 22 million black people who are the victims of Americanism. One of the victims of democracy… nothing but disguised hypocrisy. So, I'm not standing here speaking to you as an American, or a patriot, or a flag-saluter, or a flag-waver—no, not I. I'm speaking as a victim of this American system. And I see America through the eyes of the victim. I don’t see any American dream; I see an American nightmare.

--Malcolm X, from “The Ballot or the Bullet” speech (April 3, 1964)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Delmont, Matthew. “Why the Confederate Flag Flew During World War II.” The Atlantic, June 14, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/06/how-us-military-came-embrace-confederateflag/ 613027/.

“Joseph DeCastro - Recipient.” The Hall of Valor Project. Accessed August 28, https://valor.militarytimes.com/hero/2109.

Ladd, Sarah. “The Ku Klux Klan Is Planning to Hold Its Second 'Kookout' Saturday in Madison, Indiana.” Journal. Courier Journal, August 27, 2019. https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/local/2019/08/26/klu-klux-klan-holdsecond- kookout-saturday-madison-indiana/2126647001/.

Orlando, Trina. “Beachgoers Blasted for Displaying Confederate Flag Beach Towel in Evanston.” NBC Chicago. NBC Chicago, July 30, 2020. https://www.nbcchicago.com/news/local/that-flag-right-there-is-my-swastikabeachgoers- put-on-blast-for-displaying-confederate-flag-in-evanston/2314456/.

Radio.com. “'That Flag Right There Is My Swastika': Woman Confronts Group With Confederate Flag Towel At Evanston Beach, Posts Video Of Exchange: News Break.” News Break Evanston, IL. radio.com, July 30, 2020. https://www.newsbreak.com/illinois/evanston/news/1609011609928/that-flag-right-there-is-my-swastikawoman-confronts-group-with-confederate-flag-towel-at-evanston-beach-posts-video-of- exchange.

Sellers, Frances Stead. “Confederate Pride and Prejudice.” The Washington Post, October 22, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/national/wp/2018/10/22/feature/some-white-northerners-want-toredefine- a-flag-rooted-in-racism-as-a-symbol-of-patriotism/?utm_term=.37b9270997a4.

Stilwell, Blake. “What Happened When Two Civil War Flag Bearers Fought Each Other.” We Are the Mighty, April 23, 2019.

Times-Journal, Special to the. “DeKalb County United Daughters of the Confederacy Chapter Hosts District Meeting.” Journal, March 4, 2020. https://times-journal.com/news/article_0cd53a38-5e61-11ea-a2d0- d7febdd812e2.html.

![Detail: Jerry Bleem, Collateral Damage [Uncorrected], 2009, correction fluid, lint from U.S.A. flags on lint roller sheets, book form, 7.125” x 16.75” (closed); 7.125” x 33.5” (open)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c3d179a2487fdb89882a2a6/1599143100389-7A42TD77EJVT6HJHZC6Y/image-asset.jpeg)

![Jerry Bleem, Camouflaged Nationalism [Select Your Allegiance Carefully], 2009, U.S.A. flag, Thai flag, patriotic bunting, nylon cord, dimensions variable (6’ x 9’ as photographed)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5c3d179a2487fdb89882a2a6/1599144043245-0ESWDKLF0DPOPTZ8G1IV/12.jpg)